Silent Hill (1999): Fear for the Flesh

It should be noted this series will contain spoilers for every game in the series, this one covering Silent Hill in particular, as well as a discussion of the dark, sensitive topics the Silent Hill series explores, so be prepared if you’re easily disturbed.

“The fear of blood tends to create fear for the flesh.”

Silent Hill’s first line is an interesting one, as it seems vague and meaningless, almost pretentious in a way, but it’s never mentioned once in the game beyond that very first time. It’s simply the first thing you see as an opening cutscene plays, to think about before you begin playing. It should be noted it doesn’t say “fear for your flesh” or “fear of the flesh”, but fear for the flesh itself. It could mean absolutely nothing and be a really poor translation considering the game is Japanese and translations back in the day weren’t fantastic. It could mean something fairly obvious and mean being afraid of blood means you’re just afraid of being hurt. Personally, I believe it perfectly encapsulates what makes Silent Hill special.

The Silent Hill series, published by Konami, began development in 1996. Earlier that year, Capcom’s Resident Evil had been released to massive success, and Konami wanted a piece of the action. They wanted to make a horror game unlike their gothic, very classical horror feel of the Castlevania series, and more along the lines of a Hollywood B-movie, which would appeal to the United States for extra income while entering into the 3D era. However, the team assigned to make the game known as Team Silent struggled to create the game Konami wanted and were soon enough given much more creative liberty to make the game they wanted, rather than one that would be financially successful.

Silent Hill was released in 1999 on Sony’s PlayStation. The game follows a man named Harry Mason, who, on vacation with his adopted daughter Cheryl in the small lakeside town of Silent Hill, crashes his car after a child-like figure suddenly appears on the road. When he wakes up, Cheryl is gone from the car, nowhere to be seen, and seems as if she just walked away from the crash. As Harry walks into town, he notices it’s covered in a thick fog and light snow despite it being summer, with a complete lack of residents, as if the whole town has disappeared. Soon enough, however, he spots Cheryl in the fog. He begins to run after her, and while giving chase, he is led into an alley.

As he walks further into the alley, and passing through a gate, it suddenly becomes dark, and air raid sirens can be heard in the distance, as Harry lights a match. He passes a crumpled wheelchair, and what appears to be a covered, bloody corpse on a hospital stretcher, Before he comes to the end of the alley and finds himself face to face with an eviscerated body crucified on the chain-link fence, which is not even distinguishable enough to even be identified as human. As he turns to run, he is surrounded by child-sized grey creatures holding knives that quickly take him down, and he subsequently blacks out.

When Harry comes to, he finds himself in a café. He sits up quickly, and is greeted by a blonde woman. They’re both cautious of each other at first since they’re the first person either has seen in town. She explains to him that she is a police officer from the next town over and came to investigate, while Harry explains his own situation to her in return. Coming to a mutual understanding, she introduces herself as Cybil Bennett, and Harry introduces himself as well. He then gets up to leave, which she questions since they both know how dangerous the streets might be, so she gives him her gun to defend himself, and leaves the café to get reinforcements from her town.

While Harry collects everything in the café, something flies by the window which he doesn’t take notice of. He finds a notepad, which is used as a save point (Harry explains in a twist on the typewriters from Resident Evil that he wants to write down notes so if someone finds them, they’ll know what happened, which goes along with Harry being a writer) before heading to the door. Suddenly, a seemingly broken radio sitting on a table starts ringing, but as he goes over to investigate, the windows break, and a huge winged creature smashes through, attacking Harry. He quickly has to kill it, being left to wonder what the thing even is. Once he’s done, he leaves the café, and the game truly begins.

Harry Mason, the writer, father, and protagonist, waking up from the first nightmare.

As Harry walks outside, you get your first feel of the controls in a less scripted area. As was the case with many early 3D games on the PlayStation, Silent Hill uses tank controls, which essentially means the game was designed around the D-pad (the four buttons of the left side of the controller) rather than the left analog stick, which means forward on either one moves you directly forward, while moving backward moves you directly backward, and to rotate, you have to hold to the side buttons, or the stick left or right.

In most modern 3D games, this wouldn’t really work, seeing as it isn’t very precise and in general, it would be a struggle to match such stiff controls with a fully controllable camera, so instead, as with most games with tank controls, it instead uses a fixed camera, meaning the camera is usually either stuck in one place in the room you’re in, or is always directly behind you, sort of like if you were following the character or looking at them from a security camera, rather than if you were looking around as the character themselves.

This control scheme takes some getting used to since most modern games control much more smoothly and aren’t as restrained by their consoles, but they work surprisingly well despite this, especially in adding to some of the game’s tension since you might not be able to see an enemy around a corner before it’s already in front of you. However, seeing as this could be potentially frustrating to some people, seeing as you could potentially take unfair hits you couldn’t see coming, the game does have a small level of control in certain places. If you hold down the L2 button, you can rotate the camera around to see places the fixed camera doesn’t allow, and prevent enemies from being annoying rather than nerve-wracking, since you’re given a chance to catch a monster as it’s running at it rather than right as it’s grabbing at your ankles. The game does, however, have another system to make sure you know when you’re about to be attacked.

The radio is used as one of the most brilliant alarm systems in any game. As previously mentioned, the radio goes off right before the first monster attacks you, and this applies to every enemy in the game. The radio will always begin making noise when an enemy is nearby, gets louder the closer the enemy gets to you, and often plays certain music for area-exclusive enemies. On occasion, the music gets louder and significantly more intense if you’re near a particularly powerful enemy, most notably, the final boss.

The radio goes off before the Air Screamer monster attack.

Exploring the town, Harry runs into a lot of monsters, flying creatures and dogs in the beginning, and later, much more twisted beings. Like most survival horror games, he is given means of defense, but with limited ammunition, requiring you to strategize and plan out whether or not to run from enemies or fight them if they’re in the way of something important. Attacking can be a little inconvenient since you have to hold R2 to prepare a hit/gunshot, and then press X to strike/fire, which, in my experience, can be a tense race not to take a hit before you’ve even got the chance to defend yourself. There is no reward for killing enemies either. You don’t get health pickups or bullets from them, you just get to live and progress, so fighting is more for the sake of avoiding being attacked later in an area you have to return to, or in the case that you get completely trapped. Otherwise, it’s almost always better to run past most enemies that aren’t faster than you and strategize around the ones that are.

Visually, the game has poorly aged graphics at a surface level, which was more due to limitations of the PlayStation rather than for lack of trying to make them better. For its time it is very impressive in a lot of places though, especially its use of lighting, fog, and its FMV cutscenes. Takayoshi Sato, the main person in charge of visuals, worked incredibly hard on the game. In fact, he lived in the development office for two and a half years while working on the game’s CGI cutscenes completely on his own after his superior refused to credit him for his work designing all the characters. These FMVs look great for their time, capturing a surprising amount of emotion and detail that many games of this time were incapable of, stooping just deep enough into the uncanny valley that the characters are still recognizably human, but creepy and off-putting.

The whole cast of Silent Hill (from left to right, Cybil, Dahlia, Alessa, Cheryl, Harry, Lisa, and Dr. Kaufmann) in their FMV cutscene models.

Harry and Lisa in-game.

This game, unlike many classic survival horror games and early 3D games in general, opted for creating fully 3D environments rather than using pre-rendered backgrounds (essentially just still images with boundaries set so you couldn’t just walk anywhere you wanted on the flat image). While the in-game character models look pretty bad even for their time, many of the monster models are very detailed and the animations are all very smooth. Many people cite the poor visuals adding to the fear factor of the game, but personally I feel it strays a little too far into the hard-to-take-seriously territory, sometimes being unintentionally humorous in its lack of facial animations and Harry’s awkward, wobbly-legged sprint, but that isn’t to say it’s devoid of terror by today’s standards.

Beyond the controls adding tension out of the necessity of the stiff motion, the game’s use of darkness and fog was one of its most brilliant solutions to the PlayStation’s graphical limits. The system could only handle having so much 3D on-screen at one time, or the game would slow down, or the system would overheat, so a common solution was either to have small rooms or to restrict how far you could see at one time.

A Grey Child monster approaching out of the dark.

Silent Hill goes with the latter for the most part, but builds it fully into a mechanic of the game. Most of the game takes place in the dark, which, as the opening segment presents, is a transition into an even deeper nightmare than the town is already in, meaning a lot of the time you’re physically unable to see in front of you because of how dark it is, which is consequently solved by having a flashlight that shines within a certain radius around you, allowing you to see just far enough not to be blind, but not too far so that you can’t see threats immediately, just hear them on the radio.

On the outside, or before transitions into the dark, the town is overcast in a thick fog, and snow (not ash, as it is in the movie version) falls to the ground, which allows you to see a little further, but not by much. This lets you have only a little more forewarning to threats, on occasion allowing you the chance to sprint in the other direction if you can spot a monster before it spots you.

The game’s potentially anxiety-inducing visuals are also complemented by its soundtrack, composed by Akira Yamaoka, which is less music than it is just industrial noises. Most of the songs are composed of metallic banging noises, harsh percussion, static, and one of the best uses of an electric drill ever used and distorted in the final boss theme “My Heaven,” all of which play during the game’s times of panic and horror, usually surrounded by total silence or eerie atmospheric tracks like “Claw Finger” in between, or just the quiet buzzing of the radio going off.

Harsh noise isn’t the only thing the soundtrack has going for it as many of the game’s tracks are a variety of soft rock and guitar tracks used in more emotional moments such as the opening theme “Silent Hill,” “Not Tomorrow 1,” “Tears of…,” and a track called “Esperándote,” which is an Argentine Tango sung by Vanesa Quiroz and composed by Rika Muranaka. These tracks perfectly accentuate what I feel sets Silent Hill apart from other horror games of the time: Silent Hill, as a series, is deeply personal and emotional in its narrative.

The game’s story, while not as meaningful and deep as its follow-ups, still provides a strong, emotional narrative that the series now prides itself on. The story revolves around a girl named Alessa Gillespie, who was a psychic. She was bullied as a child and abused by her mother (which is explored further in Silent Hill 3 and Origins), Dahlia, who was the leader of the town’s religious cult, and soon saw her as the best option to birth the cult’s God. She performed a ritual in her house on Alessa to impregnate her with the god, but soon enough the ritual set Alessa and the entire house on fire, leaving Alessa with a charred body, but seeing as the ritual had succeeded, she was now immortal despite her burns, and left in a constant state of suffering.

Alessa, burnt and wrapped up in bandages at age 14.

However, as the ritual is performed, she splits her soul in two and manages to leave her other half in the form of a baby on the side of the road where Harry and his wife find her. His wife dies young, but his relationship with Cheryl (the other half of Alessa, which Harry is unaware of) grows, where he finds her to be the most precious thing he has. This continues into the game’s plot, with the aforementioned loss of Cheryl, and exploring the town. All the locations in the town are connected to Alessa’s suffering, between the elementary school she went to, to the hospital she was brought to after being burned, to Nowhere, the deepest, darkest part of her psyche, a mess of locations filled with her worst memories, and that’s where much of the horror of the first game and rest of the series, as the next two games would set the standard for, came from. The real horror all comes from Alessa’s head.

Alessa, as a character, isn’t given much time to be explored in the game, since a lot of her background is found in notes around town, the game’s novelization, or later games. Regardless, you still manage to feel completely sympathetic towards her in the first game alone. The abuse she suffers from the powers she didn’t choose to be born with, especially from her mother, is saddening. Harry reads notes around school that she came to school every day with bruises, and, the town being completely under the cult’s control, there was nothing her teacher could do to get her out of her home. She was also strongly religious because of her mother’s influence, believing that God would one day cleanse the Earth with fire. and having the best intentions in mind, believed the Paradise this brought would lead to a world of happiness, where she could finally have the happy life she’d never been allowed to have, and parents that loved her.

As an older girl, and certainly after she was burned in the name of her so-called God, Alessa very quickly lost her faith. At school, she was bullied by her schoolmates. Harry finds notes on her desk, with the words “DROP DEAD” carved into it, and through the notes, it is found how the abuse from her mother, Dahlia Gillespie, worsened, likely seeing her as an abomination against God or as some sort of witch, but still raising Alessa to be a part of the cult. Soon she came to realize her daughter was the perfect surrogate mother for the rebirth of the cult’s God. In the past, the cult unsuccessfully kidnapped young girls and attempted the impregnation ritual, likely due to a lack of the strong spirituality God’s birth required.

As previously mentioned, the ritual does succeed in part, leaving Alessa to slowly recover from her immeasurably painful wounds while her mother kept her in the basement of the town’s hospital for seven years. She is cared for by a nurse named Lisa Garland, who is seemingly the only person in the town who treats her with any sort of kindness despite being horrified of her burns and confused as to how she’s even still alive. Lisa is soon hooked on drugs by the head doctor at the hospital, Dr. Kauffman, and dies not long before the events of the game, but meets Harry as a ghost who doesn’t know she’s dead, trapped in the town. Alessa, alone and unloved, seethed in her near-catatonic state, and in pain, engulfed the town in her nightmares, leaving some trapped within a horrific reality between the real world and the deepest depths of her fears, which is a great explanation for the game’s monsters.

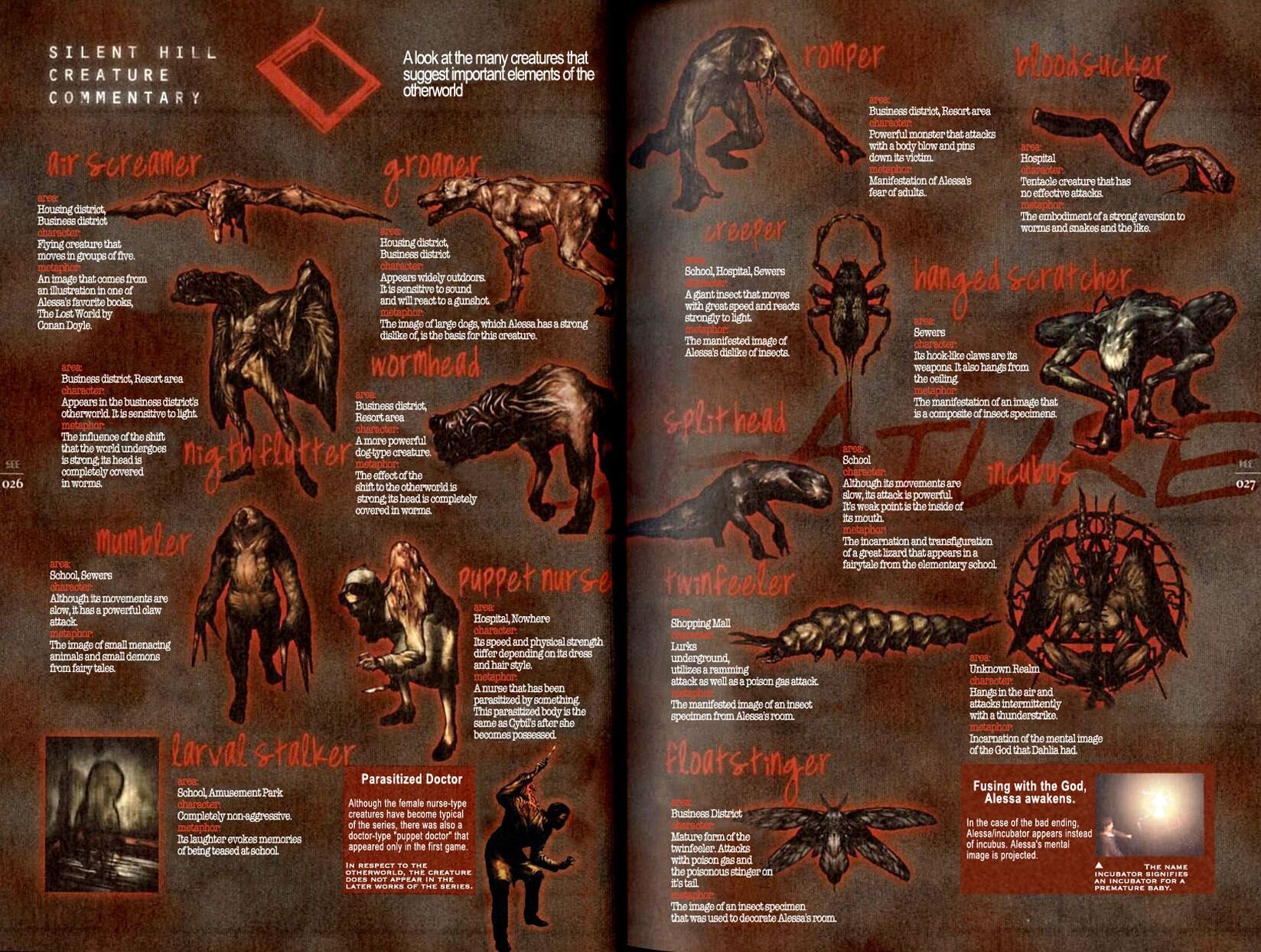

The creatures of Silent Hill, while just generally scary ideas for horror game enemies, are cleverly connected directly back to Alessa. Alessa is scared of animals, so the town manifests them as twisted, skinless canines and giant grasshopper-like creatures, as well as three of the bosses being a lizard, larva, and moth. Alessa is afraid of adults, doctors, and her classmates, so the town manifests horrible ape-like creatures that are nearly inescapable, parasite-infected, slumped over nurses, and knife-wielding deformed child-like creatures. Alessa’s favorite book, Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, manifests in the form of dinosaur-like monsters, literature also being a big inspiration for the names of streets, all of them being named after sci-fi and horror authors, which connects back to Harry being a writer as well.

All the monsters in-game.

I didn’t connect to Silent Hill emotionally as much as the following two games, but the suffering of Alessa brings a significant amount of emotional baggage for a character who only gets a couple of minutes on screen throughout the entire game. I felt bad for her throughout the game, especially by the point you get to Nowhere and see firsthand the terror her mother put her through as a child, you feel her fear as she just wants to feel loved and cherished, how she was destined to be alone from the day she was born, completely out of her control. So much of her character is read through subtext as well, so you might not even grasp the true extent of her abuse, which made me want to go out of my way to look for signs of her and get the good ending so Harry can give her the happy life she deserves.

Silent Hill, as a series, pioneered psychological horror games so well because of how immediately it accomplished its more depressing, realistic tone in contrast to its more spiritual, fantastical elements. Where Resident Evil, and most other horror games of years past, were essentially interactive B-movies with zombies, vampires, and creepy deformed men with comically large scissors, usually having action heroes or slasher movie girls as protagonists, Silent Hill brought a certain maturity, despite the gory nature of horror, which hadn’t been explored before in many horror games, exploring real-life, personal atrocities, like abuse, or drug addiction, and gives them a platform to be confronted in a way that wasn’t hamfisted or even directly important to enjoying the game if you didn’t care about the story, making things that were already scary have an extra touch of creeping dread with their connections to the saddening life of a traumatized little girl, hated by a world she had no control over.

Eventually, once you get to the end of the game, Dahlia Gillespie, turning out to have been tricking Harry into capturing the half of Alessa’s soul inhabiting Cheryl, fuses the two halves back together. Depending on whether or not you’ve done one of the game’s sidequests involving Dr. Kauffman, the God will possess Alessa and you’ll have to fight a glowing, angelic deity called The Incubator (insinuating this form is still just the carrier), or the doctor will show up to betray Dahlia and throw an exorcising liquid on The Incubator, causing the hateful, premature God to instead rip its way out of its mother’s womb as a more suitably horrifying abomination called The Incubus, a monstrous demon intent on performing the cleansing of the human race should it make its way out of Alessa’s nightmare.

The Incubus bursting out of the Incubator.

Either way, Dahlia is struck down by heavenly lightning, the monster having fed on Alessa’s hate, and nobody fueled that hatred more than her mother. Soon enough, Harry defeats either the Incubus or the Incubator, kicking off one of four endings: Good+, Good, Bad+, and Bad. In the Bad endings, where you fight The Incubator, the deity, now back to being Alessa, gets out one last “Thank you, Daddy. Goodbye,” in an oddly heartbreaking, child-like voice Harry recognizes as his daughter. Harry will then collapse to the ground in despair, having lost everything, crying out Cheryl’s name as Nowhere collapses into flames. In the Bad+ ending, it even cuts to Harry still sitting in his car, dead after the crash, the events of the game having been a pre-death delusion.

In the Good endings, where you fight the Incubus, the Incubator, back to being Alessa, uses the last of her power to give Harry a piece of herself, another baby, and a chance to start over, and, overexerting herself one last time, saves Harry from the collapsing Nowhere, and he finally escapes the town. In the Good+ ending, Harry is joined by Cybil Bennett, who you can save from possession in a boss fight against her earlier, and Dr. Kauffman is pulled into the depths of Nowhere by the phantom of the nurse who took care of Alessa, Lisa Garland, finally getting vengeance for her drug abuse spurred on by the doctor. Regardless, the nightmare finally came to a close, and yet, it had just begun.

Silent Hill, beyond its relatively poorly aged graphics and awkward controls, is still a phenomenal game, and it’s no wonder it was such a rousing breakthrough. Nothing before it had ever captured the feeling of truly feeling like you were trapped in someone else’s hell, a place where fear, blood, and darkness were the only reality there was, if there was any reality to truly speak of. Beyond its outwardly grungy, visceral nature, it's an emotional story of abuse and isolation, feeling desperate and alone in a hateful world, and overcoming it with the help of someone you mean the world to.

Harry is an everyman, meaning he’s easy to identify with, an ordinary and kind man who wants nothing more than to find the daughter he loves more than anything. He’s your link to the nightmarish town, and through his blank slated character, you become immersed in his journey to save his daughter and end the suffering of Alessa. With this girl, loved as if she was Harry’s own flesh and blood, you find something you truly want to protect. In this journey, survival is not for you, but instead, as the loving father she’s always wanted, you do it for her.