Silent Hill 2 (2001): In Our Special Place

Preceded by The Silent Hill Series Part 1 (1999): Fear for the Flesh.

It should be noted this series will contain spoilers for every game in the series, this one covering Silent Hill 2 in particular (which completely revolves around its extraordinary narrative that’s worth experiencing with zero expectations going in), as well as a discussion of the dark, sensitive topics the Silent Hill series explores. If you’re easily disturbed by certain topics, use discretion when reading this review because 2 is the most realistically dark game in the series, with a lot of disturbing themes.

Secondarily, this review is quite long, so I’ve made a Table of Contents for each of the major locations, plot points, character introductions, and topics, and each section will have a Back to Top button that’ll bring you back to the beginning of the summary and the Table of Contents for ease of access.

Angela - Wood Side Apartments - Eddie - Laura - Pyramid Head - Maria - Brookhaven Hospital - Silent Hill Historical Society - Toluca Prison - The Labyrinth - Abstract Daddy - The Meat Locker - The Lakeview Hotel - The Music Box - The Video Tape - The Burning Staircase - Pyramid Heads - Endings - Crime and Punishment - (Summary Ends Here.) - Sound and Music -Visuals - Terror vs. Horror - Conclusion

(Summary Begins Here.)

Silent Hill 2 does not open with an immediate line like the vague warning of Silent Hill’s “fear for the flesh,” but with a visual.

A man stares into a mirror, the shadows too murky even to see his eyes. He places a hand to his expressionless face, as if he’s seen a ghost in the reflection. As he pulls away and groans in exhaustion and the game switches from CGI to the in-game graphics, the camera tilts disorientingly as the man mutters to himself, “Mary… could you really be in this town?” This opening presents uncertainty and uneasiness, unlike the disturbing implications of the first game. In Silent Hill, reality was dark, bloody, and disgusting. Silent Hill 2 questions whether or not what you perceive is reality, and whether or not you’re ready to face it.

Horror, especially psychological horror, is one of the greatest vessels for telling stories of deeply personal, heart-wrenching tales. The darkest parts of humanity and the psyche can be explored with grace and caution or with all the care and precision of a bulldozer. Films, like the previously reviewed Jacob’s Ladder, can be some of the most disturbing, yet heart-warming and bittersweet movies ever made. With the advancement of technology, video games were slowly able to catch up to their cinematic horror counterparts.

The first Silent Hill is one of the first examples of psychological horror making its big break in games. Beyond its supernatural surface, the plot was a touching story about abuse, paternal love, and finding compassion in the worst of environments. Its psychological elements, namely the exploration of the psyche of Alessa Gillespie, weren’t put at the forefront, but instead went for a much more cinematic approach where exposition was all subtext, and the actual underlying themes were all but optional if you wanted the full picture of what was going on beyond the thick fog and snow.

Whereas the first game has more of a legacy of being the most revolutionary game of its kind rather than the best (similar to the first Resident Evil game), Silent Hill 2 is one of the most legendary games, let alone horror games, of all time. After the surprise success of the first game, 2 was given a significant upgrade in both budget and creative freedom for most of its development, a rarity for this series and the chokehold Konami has over it.

From the first moment of gameplay, Silent Hill 2 feels different. The man from the intro exits the bathroom, asserting himself in reality. James Sunderland is a young man around 30 years old. He’s almost conspicuously average looking with pale green eyes, parted blonde hair, and a fairly unathletic build. He wears a green military jacket based on the one Jacob Singer, played by Tim Robbins wears in Jacob’s Ladder (same initials as well), a gray polo shirt, and plain blue jeans.

James Sunderland and Jacob Singer from Jacob’s Ladder (Tim Robbins).

If you can imagine the most unremarkable man imaginable, you can probably imagine James. As he looks over the local Toluca Lake, he reads a letter he recently received from his wife Mary in the series’ most iconic quote:

The issue is, Mary has been dead for years, from a terminal skin illness. James still holds out a desperate hope that somehow it's true they will meet again. There’s a certain discomfort and eeriness to this game’s opening that wasn’t present in the first game. The first game sets more of a dark, Twin Peaks-esque mystery with its CG intro, giving you nothing but visuals and the most vague of information, while this game gives you all the information you need to begin but leaves you feeling like something is just… off. Things don’t add up, and the main character knows this, but doesn’t question it, which I believe is Silent Hill 2’s biggest split: James is not an everyman.

In the first game, you’re shown the conflict, and every horror is introduced to you, the player, at the same time as Harry Mason, the main character. He’s a stand-in for you, and his identity is not essential to understanding the plot unless, again, you want the psychological elements to be more dense in its small details. James is different. From the beginning, James knows more than you. This juxtaposition immediately breaks the everyman trope, which becomes slowly more and more evident as the story goes on.

Angela

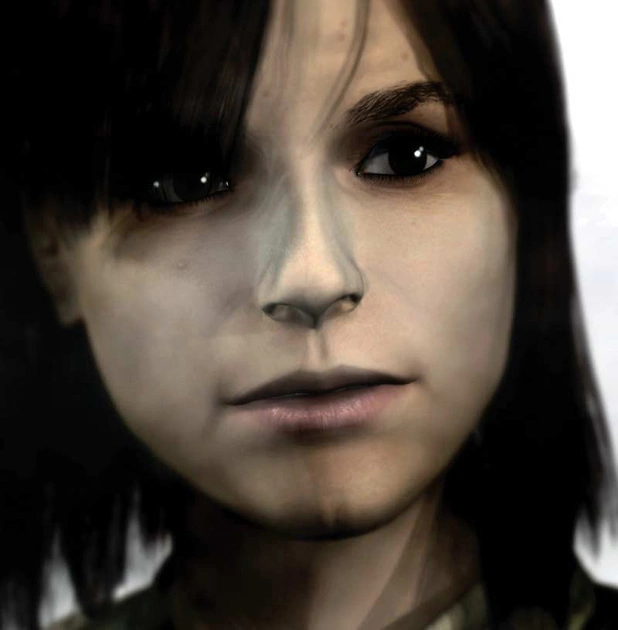

James, as well as all the other characters in the game, are uncomfortably awkward people. The first character you meet is a teenager named Angela Orosco; she was named after Sandra Bullock’s character from the 1995 movie The Net, Angela Bennett, and resembles the actress quite a lot. Strangely enough, she’s actually on the box art of the game rather than James. After voyaging for a while through a thickly forested, foggy pathway, unnervingly quiet (although, if you listen very carefully, you can hear something shuffling around in the foliage) you come across a graveyard where Angela stands, while shiftily looking around.

Angela Orosco and Angela Bennett from The Net (Sandra Bullock).

James greets her, which startles her. He apologizes and asks if she knows the way to town. She points the way, but mentions the town is dangerous, although James cuts her off before she can say why. James says that he doesn’t really care if the town is dangerous, since he’s looking for someone. Angela says she’s looking for someone too, her mother - although at first she refers to her as “mama'' before correcting herself. They part ways, wishing each other well on their searches.

This first dialogue presents one of the biggest strengths of the game, and yet also one of the main criticisms of the game at the time. The voice acting is scattered in terms of delivery; lines are sometimes unemotive and stilted, and frequently have awkward pauses and strange gaps between statements. However, unlike the first game’s of-the-time subpar voice acting and direction, the clear intention of this emptiness is highlighted by emotional outbursts from the characters that show they clearly can act emotive, but generally remain monotone. It’s as if they’re all walking a tightrope between controlling themselves and completely snapping, only briefly allowing their true colors to show through.

It's another element of discomfort and uneasiness, coupled with the relatively aged look of the game and the motion capture work that brought the animations to life, that makes what would otherwise be relatively bad voice acting from people who were not really voice actors into an extra layer of creepiness. Each character is deep in the uncanny valley, are written realistically, designed realistically, but just detached enough in their stilted vocals and just slightly off-looking faces to be unsettling.

Continuing on, James finally gets into the town, which is just as foggy as it was in the forest, if not more so. You can get lost pretty quickly in the town, but for the sake of practicality, so you don’t just wander around aimlessly, the town will often put obstacles in the way of alleys and streets to vaguely guide you in the way you’re supposed to go. The town itself can eerily and supernaturally disappear depending on where you need to be. Exploration isn’t all downsides though, as you’ll find healing items, weapons, ammo, and small pieces of lore scattered around town. It’s not like you’re alone in the streets.

James comes to a street corner where he finds a dark red streak across the asphalt. Staring deep into the fog, he sees a figure limping away. James follows the figure to see if they’re okay or get directions, and soon finds himself at the end of an alleyway in a small tunnel. As you approach, you can hear a radio buzzing loudly. For those that played the first game, this immediately sparks caution. James, though, has no idea what that noise means, and as he picks it up and tries to fix it, a dark figure rises up behind him.

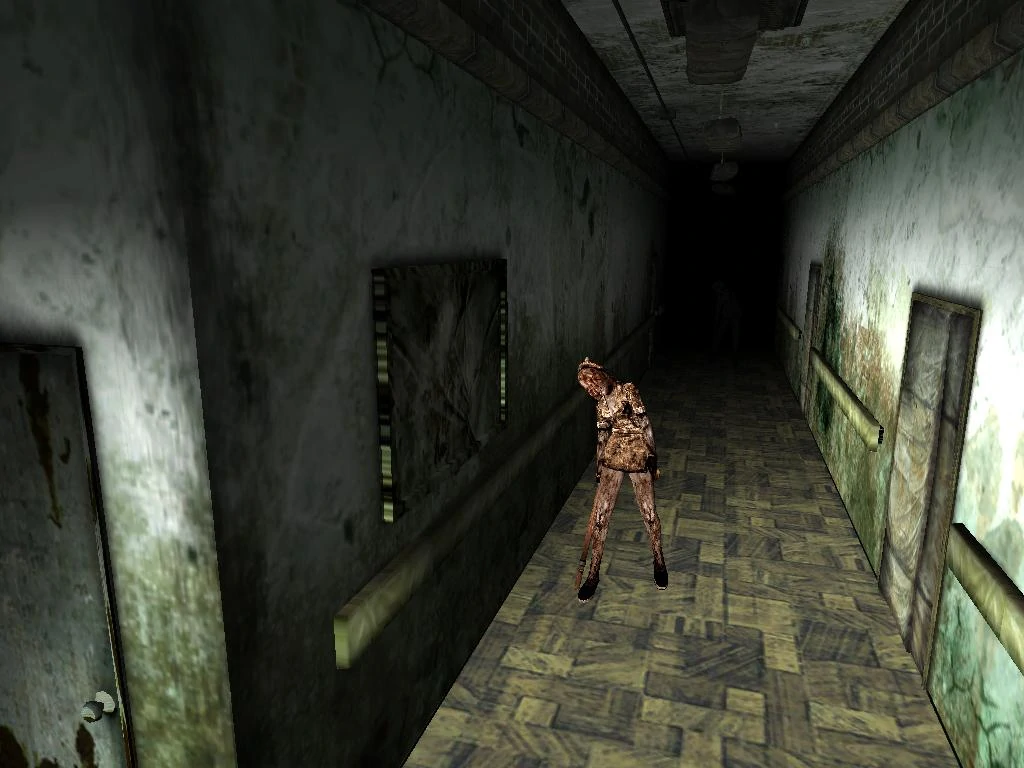

It looks human, silhouetted in the gray fog, but as it turns and you see it fully. It’s clear that whatever it is, it’s monstrous. It’s a tall, feminine creature with no discernible face with long, lithe legs ended with platform shoes infused to the creature’s ankles, and arms that seem to be contained within the very skin of the monster, like a grotesque, fleshy straightjacket. James, who is trapped with his back to a fence, grabs a plank in self defense.

Combat is about the same as in the first game, readying an attack with a trigger button before swinging with the action button. The targeting is a little better, but the combat is still just as haphazard and awkward in a way that always makes victory much less sure than much cleaner combat would be. Story-wise, similar to Harry from the first game, James is competent but not exceptional in a fight, being an average younger man and not a trained fighter. He awkwardly swings at the monster, called a Lying Figure, knocking it to the ground in a pool of deep red blood. It vocally disgusts him, and he exits the tunnel, taking the radio with him.

The Lying Figure.

Before he proceeds, he fiddles with the seemingly broken radio, when suddenly a woman speaks from it in broken sentences, the static cutting her out. James recognizes it as Mary before it goes quiet again and takes it with him, realizing it could lead him closer to her. More importantly, it makes noise to warn you of nearby monsters, a brilliant system carried over from the first game.

Wood Side Apartments

After the intro, the next hour or so of the game revolves around exploring a decrepit apartment. This sort of tutorial area teaches you how to deal with monsters and get through any given area. A series of notes scattered on the streets of Silent Hill tell you the demons are attracted to light and sound, and can be avoided if you stay quiet by not running, and staying in the dark without a flashlight when you get in the apartment. This isn’t a certainty though; if you get close enough to them, they may find you anyway, and with how cramped and claustrophobic this area can feel, you need to learn how to fight them in case you reach a situation where you cannot simply sneak past the demons.

Every given area gives you the freedom to explore wherever you’d like (within the aforementioned supernaturally placed boundaries), but some rooms won’t be open without a key, which begins the Silent Hill gameplay loop of getting a key item to solve a puzzle to get access to a new area. Puzzles are surprisingly thoughtful and not as cryptic as the first game’s a lot of the time and require checking the environment around you and putting a good bit of thought into what little clues you’re given, often in the form of a riddle. They don’t hold your hand at all, sometimes to a fault, with a rare few puzzles being too vague to figure out without at least a little trial and error with using whatever items you have (or a guide if you’re as terrible at riddles as I am). This can be a bit of a tedious process with how slow loading the menus can be on the original console.

The Wood Side Apartments, exterior and interior.

Eddie

As you make your way through this area, you come across two new characters. Eddie Dombrowski, named after Eddie Murphy and possibly Louie Dombrowski from Twin Peaks. He obviously resembles neither. He is a heavyset man who wears a baseball cap backwards, cargo shorts, and a blue and white-striped polo shirt. You find him in the bathroom of an apartment with a bloodied corpse lying in the refrigerator. Eddie claims he didn’t do it, but considering he’s in the process of barfing his guts out into the toilet in the very same apartment, he seems like the most obvious suspect.

James is a little questioning at first, but soon enough drops his suspicion of Eddie when Eddie says he’s been seeing monsters too. James asks if the town “called” him, like it did for himself, and Eddie simply replies, “You could say that.” James leaves as Eddie continues hurling.

Laura

Laura, on the other hand, is a blonde, obnoxious little girl in overalls who tends to get in the way of James throughout the game. She was named after a young girl of the same name from a book called No Language But a Cry by Richard D’Ambrosia, a real story about an abused girl overcoming her struggles, and her outfit, as well as Mary’s, were likely based on characters from the movie Con-Air.

She’s first seen kicking a key out of James’ grasp, laughing at him as a prank before running away. For the time being, how she’s still alive remains a mystery, but one of the clips in the intro shows her with Eddie, insinuating he gave her a ride to town, though why or how they met remains a mystery.

Laura, Laura compared to Casey Poe from Con Air (Landry Allbright), and Laura meeting Eddie.

You also come across Angela again in one of her many fantastic scenes. She’s laid down, and holds a knife precariously near her throat as James walks in. He immediately understands what’s happening. He tries to talk her down from suicide, but she first says that it’s what the two of them both deserve, before James immediately backs off and tells her he isn’t going to harm himself. Mockingly, she says, “Are you afraid?” before apologizing. James forgives her and changes the subject.

The next few exchanges sound like two people having completely different conversations as James asks about her missing mother, and Angela mumbles deliriously and questions James, remaining untrusting of him. Eventually, she gets up to leave. James offers to come with her, but she says she’ll only slow him down, so instead he offers to hold her knife so she doesn’t think about using it on herself again. She is about to hand it to him, but suddenly screams and turns it towards him, muttering “I’m sorry, please don’t. I’ve been bad,” before awkwardly leaving the room in one of the first insinuations of the reason she’s in the town. James takes the knife with him, albeit confused.

The mirror scene.

The apartments also give you an idea of the type of scares Silent Hill 2, as well as many of the following games, have. In the first Silent Hill, scares were generally very non-eponymous, usually being pretty loud (between the industrial, metallic droning of the music, the bloody, visceral otherworlds, the locker jumpscare, and the sounds of screeching monsters and the loud alarm of the radio). Silent Hill 2 is a lot more subtle in its dreary horror. I wouldn’t say it’s as terrifying as the first game, but it always gives you this constant feeling of uneasiness, this uncomfortable pit in your stomach that only swells till its climax.

Pyramid Head

One of the greatest moments in the game, or any game ever, is the introduction of Silent Hill’s most infamous resident: Pyramid Head. This is a moment not of bombastic terror like that of Nemesis from Resident Evil 3: Nemesis, or the first enemies of the first Silent Hill shanking you in a back alley or crashing through a window, but a brief few seconds of intense unease.

At one point, as you’re walking through the apartments after solving a puzzle, you come to a crossroads in the halls when you hear the cry of a baby, deep down the dark hallways to your right. You can choose to ignore it, but by this point it’s where you need to go, so you begin walking down the hallway.

Your radio begins going off, and at first it may seem like just another enemy, but a red light dimly begins to cover the floor as you get closer and closer, and the radio increases in volume until you come to the metal bars at the end of the hall. Behind them, his massive pyramidal helmet glowing a dim red, is the Red Pyramid Thing himself. He doesn’t attack you. You can’t interact with him. Nothing happens.

He just stares through the bars as your radio blares at you, practically begging you to leave. Either mildly unsettled or frustrated at your inability to do anything, you go into the room to your right, get some supplies and leave. He’s gone when you get back.

For being the series’ spiritual mascot, Pyramid Head’s introduction isn’t a big boss fight, or a jumpscare, or a chase scene, it’s just him simply being there, and then disappearing. You now know he’s SOMEWHERE in the building, you know you’ll see him again. But when? Where? How? He doesn’t even attack you at first, so what’s his purpose? Is he going to be a Nemesis style chaser, just a recurring boss, or maybe have more significance?

Silent Hill 2 leaves you with such uncertainty and unease just by making its most significant monster stand there, doing absolutely nothing, which I think illustrates the brilliance of every single choice made with how the game is presented, and how it chooses to make the player feel. You may not be afraid for every moment of Silent Hill 2, but you’ll never feel an ounce of comfort either.

After another encounter with Pyramid Head (he assaults a duo of newly introduced Mannequin monsters in an apartment as you watch from a closet in a reference to the film Blue Velvet), you eventually have a first boss fight with him in the fire escape after assaulting a Lying Figure, again in a very suggestive way. Boss fights still aren’t really Silent Hill’s strong suit, or a lot of pre-Resident Evil 4 survival horror games, so it’s more or less just running back and forth in a room either shooting at him enough or avoiding him for a few minutes until he goes away, avoiding swings from his iconic Great Knife (portrayed in this game as half of a pair of scissors or shears as stated by Masahiro Ito, but also strongly resembling Angela’s knife), or his grab if you get too close, during which he apparently sticks out a tongue through a hole in his helmet to do… something to you.

The Blue Velvet reference, Pyramid Head’s abuse of other monsters, and Pyramid Head’s tongue.

Maria

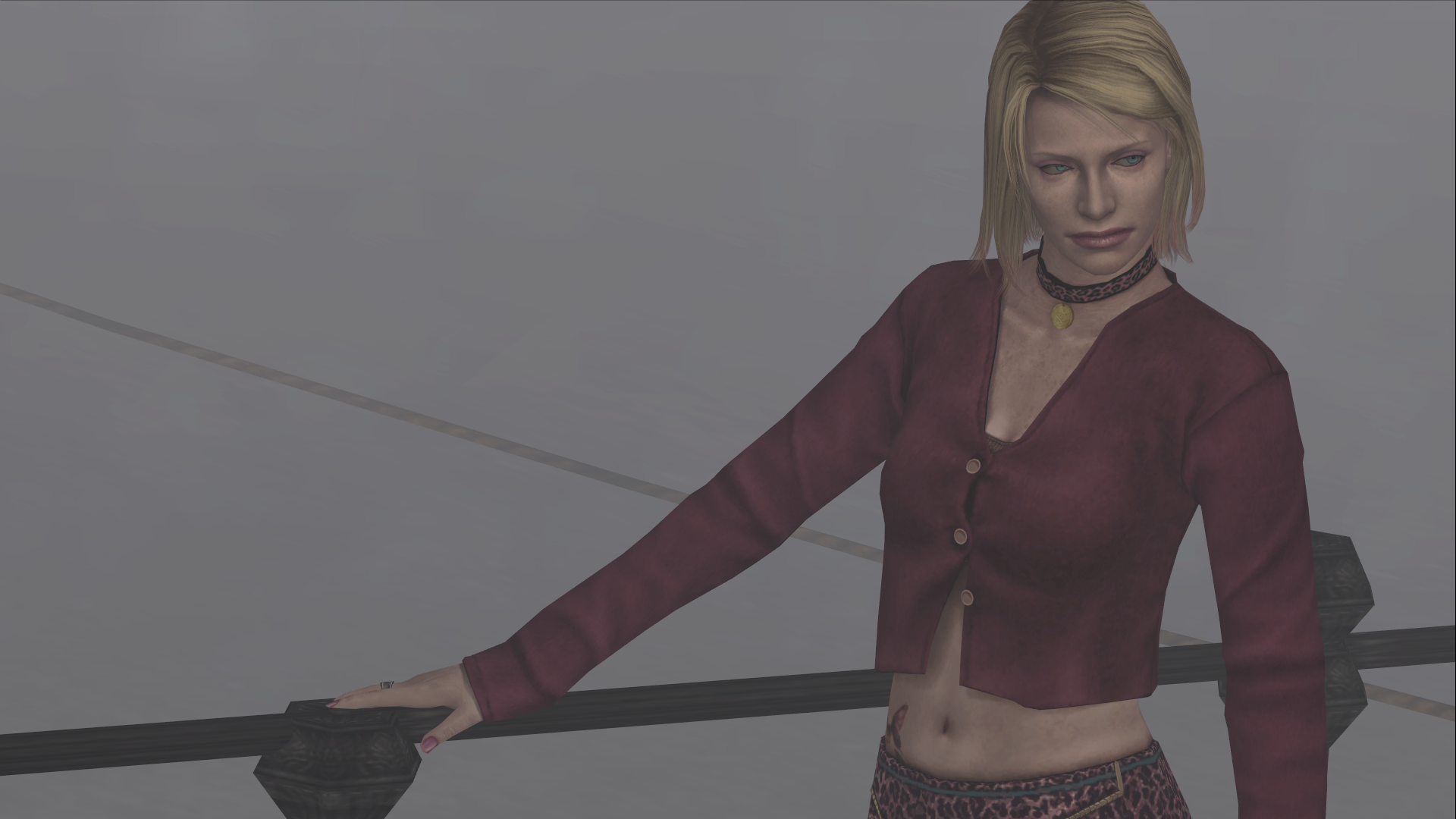

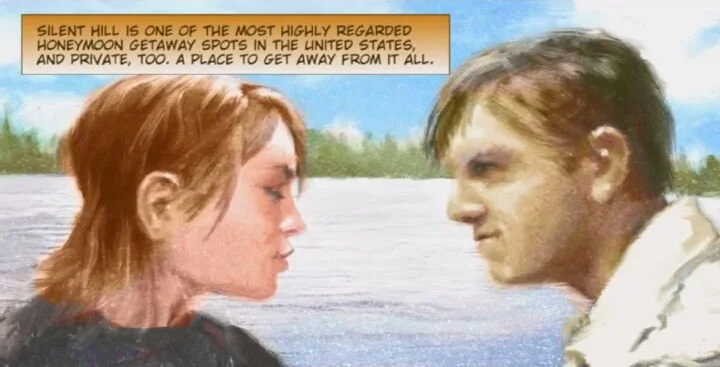

Regardless, you survive, and he retreats for now, as an ironically water filled fire escape drains, letting you finally leave the apartments. This lets you finally get to James’ first suspicion for a potential “special place,” Rosewater Park, where the couple spent a day together just staring off into the water of Toluca Lake. There, he finds an odd sight in the deep fog: a woman who looks and sounds exactly like Mary, but with bleached hair and the outfit of Christina Aguilera from the Kids Choice Awards in 1999. He’s confused, but she introduces herself as Maria, another odd coincidence.

She has a much more sultry and flirtatious personality than his wife, proving she’s not a ghost by bringing James’ hand to her chest, much to his embarrassment and discomfort. He asks if she saw Mary, but she says she hasn’t. She does question whether the park was really their only “special place” though. He has a brief memory of a hotel, The Lakeview, to which she flirtatiously teases him again. She points the way and he begins to leave, but her personality suddenly shifts to a much more serious tone as she berates him for thinking of leaving her alone with all the monsters around, before cutting him deep, remarking that she looks like Mary, and surely, he’d let her come along with him, unless, of course, he hated the real Mary. James snaps back immediately, and much to his chagrin, allows Maria to tag along.

Maria, and Christina Aguilera at the Kid’s Choice Awards 1999.

After a bit more exploring, Maria, now following you around and being capable of dying, which can greatly affect your ending depending on how well you take care of her, you make it to Pete’s Bowl-O-Rama, with Maria staying outside. Here, you meet Eddie again, who, despite the danger, can just sit around eating pizza, to James’ disdain. Laura had just run out the back door as well, so James leaves Eddie to his pizza to make sure the girl is okay.

Maria says she saw her pass by and wanted to pursue her to make sure she was alright as well. Laura slips through a back alley neither of the adults can fit through, so they have to take a shortcut through Heaven’s Night, a stripclub that Maria has a key for, presumably because she works there as a dancer.

Brookhaven Hospital

Once they come out the other side, the two see Laura entering Brookhaven Hospital, easily the most intensely nerve-wracking area in the game, as well as the most recognizable. The first game’s hospital, Alchemilla, wasn’t really too aesthetically different from the rest of the game’s rust and blood in the otherworld, while the fog world’s aesthetic was just a fairly normal hospital. Brookhaven, on the other hand, is unsettling even when it’s in a normal state. Hospitals, I find, are creepy places as soon as you dim the lights, and Brookhaven barely has a single light on your entire way through.

The hallways are long and dark, but broad unlike the apartments. Instead of claustrophobia, Brookhaven uses blank, open space. You can see ahead of you just far enough to where you can maybe make out the glistening of an enemy’s flesh and hear the radio going off, but the enemies introduced in the hospital, the Bubblehead Nurses, are so much more aggressive than the last few that those few seconds of anticipation almost make you panic more as you wait for them to rapidly stumble towards you.

They’re difficult to exchange melee blows with since they hold rusty pipes and knives, but are also too fast to avoid with much ease. However, you still practically have to turn every corner blind with the fixed camera, so by the time they're close enough to hear you’ll likely be seconds from being beaten or slashed anyways. Brookhaven is a masterfully designed locale that combines both dangerous monsters and a floor plan designed to freak you out. It’s also one of the longest areas, having twice as many floors as the apartments, so you’ll be stuck in this hellscape for quite a while.

Brookhaven Hospital, exterior and interior, and the Bubblehead Nurses.

As you travel through the hospital’s hallways, Maria suddenly begins to feel ill and has to take a rest in a sickroom while you explore. Heading to the roof, you explore momentarily, and can grab a diary that contributes to one of the endings, but there’s nothing else up there. However, as you try to leave, a familiar sound of metal on concrete leers close, and Pyramid Head appears again whacking James with the blunt part of the Great Knife, knocking him off the roof and into a new area.

Before long, you run into Laura again, and finally speak to her about Mary, who she seems to know. However, James yells at her after she claims Mary has been alive for the last year, opposing James’ belief that she’s been dead for three years. Laura gets upset and says there’s a letter from Mary in the back of a hospital room. James, tentative but desperate, enters the room before promptly getting locked in the room by Laura. Monsters called Flesh Lips - a mass of flesh within a bed frame, legs dangling down with a pair of large, feminine lips set between them - swing down from openings in the ceiling, and another boss fight takes place.

The Flesh Lips.

After this fight, the hospital goes through an Otherworld transition and you’re transported elsewhere. Otherworld transitions in Silent Hill 2 are significantly different from the ones in Silent Hill, mostly in aesthetic, but also in subtlety. The Otherworld is Silent Hill was dark, hellish, and grungy, with flesh, blood, and metal comprising your surroundings.

Silent Hill 2 instead has a theme of deterioration, with normal surroundings now being broken down and flooded, floors and walls rotting, broken glass scattered haphazardly. As you progress further and further through levels, they only get more and more worn down and otherworldly, sometimes more like a dream, and sometimes more like a nightmare.

The Brookhaven Hospital Otherworld in progressively worst states.

You return to the room you left Maria, only to find her missing, and a strange, unsettling breathing sound filling the room, but before long you find her in the basement. James is relieved to see her, but doesn’t express it with any sort of urgency, which provokes Maria into another massive mood swing. She yells at him angrily, accusing him of not caring whether she lives or dies and abandoning her. James waits patiently until she calms down, and they make up to continue searching for Laura.

During this brief period of time, there’s a long elevator ride down from the third floor with Maria, which leads to one of my favorite moments in the game: The Trick or Treat Quiz Show. An announcer’s voice will suddenly cut in on a speaker somewhere with applause and cheering. He announces that the game is a simple enough trivia quiz, and you’ll be either be rewarded or suffer punishment for answering correctly, and says that today’s competitor is, somehow knowing, James. It asks three questions: the name of the amusement park in Silent Hill, the name of a murderer mentioned in a newspaper clipping you can find, and the name of one of the first streets you take in the game. It’ll tell you to collect your prize in the storeroom on the third floor, and cuts out. The character’s are just as befuddled as the player probably is.

If you go to the storeroom, you’ll find a box, which contains some very helpful supplies, but if not, you’ll get sprayed down with chemicals of some sort that hurt you, and can’t try again. It’s a weird moment in this otherwise pretty serious game, but I think one of many reasons Silent Hill 2 and 3, are so charming is that they aren’t always deadpan and know when to have brief moments of levity. From Eddie eating pizza in the middle of town, to the game show sequence, a number of moments in the third game that I won’t spoil until I get to it, to all of the joke endings, Silent Hill is really great at balancing brief, almost sitcom-esque moments with how disturbing and grim they otherwise can be.

As the two make their way through the basement, Pyramid Head returns, and chases them through a maze, always slightly slower but somehow increasingly closer and closer with each screen. Getting to the end, an elevator lies in wait, which James makes it into. Maria, however, gets grabbed by Pyramid Head, and after one final attempt to make it into the elevator after him, reaching a hand in, the monster runs her through. Her hand recedes through the door as the beast pulls her back, and James falls on his knees, feeling like he’s lost his wife all over again.

Before and after the death of Maria.

With Maria dead, James can’t do much but continue onward. No longer interested in finding Laura for the time being, he decides to get back to trying to find Mary. A note tells him to go to the Historical Society, which was previously locked, and find the key hidden under a statue in Rosewater Park. Finally, he gains entrance to the Silent Hill Historical Society. Plot-wise, not a lot happens in the main building, which is essentially a museum dedicated to Silent Hill’s history, but it does give us some of the first lore of the town’s deeper, darker past.

Silent Hill Historical Society

The Silent Hill Historical Society, exterior and interior.

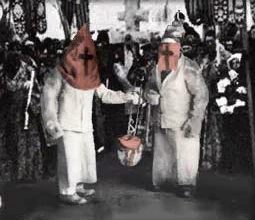

Most notably for this particular game, we see a painting and a photograph. The painting, titled “Misty Day, Remains of the Judgement”, depicts Pyramid Head holding a spear with a number of hanged corpses in cages behind him. The photo on the other hand, titled “Crimson and White Banquet for the Gods”, depicts Silent Hill’s executioners: red hooded, white-robed men. According to Takayoshi Sato, Silent Hill was where neighboring villages sent their prisoners to be executed away from cities, and executioners would wear hoods so as not to witness the killings. Silent Hill 2 all but ignores the cult plot of the first game, but in little ways still acknowledges the town’s occultism and deepens just how far back the horrors of the town extend.

James, during his vacation with Mary, had visited the Historical Society and saw the photograph before, which led to how James sees Pyramid Head, and how the town manifests “Misty Day.” In a later game, Silent Hill: The Arcade, an on-rails shooter, we see the painting again with a different version of the abstract, monstrous executioner, either being a continuity error or insinuating the painting appears differently to other people.

“Misty Day, Remains of the Judgement”, “Crimson and White Banquet for the Gods”, and the alternate version of “Misty Day” from Silent Hill: The Arcade.

“Death by Skewering,” depicts a number of Lying Figures speared on tree branches, which depicts the death of prisoners by way of spear, since they were allowed to choose their method of execution. Assumedly, this painting is also much less abstract in reality, but gives insight into lore. James’ manifestation of an executioner figure and spearing specifically is significant, but I’ll get into that later.

After briefly exploring the Historical Society, James finds a staircase that goes on for only about thirty seconds to a minute, but feels like forever, the sound of a droning boat horn through the dimly lit, rustic stone stairway. As you come out the door at the bottom, James finds himself in Toluca Prison, an old correctional facility that the Historical Society was built on top of after it was torn down. This is one of my favorite areas in the game, being the most abstract area in Silent Hill 2.

Toluca Prison

While relatively short, it left the greatest impression on me in terms of how well Silent Hill 2 continues and in ways expands upon Silent Hill’s at times surrealist approach to level design, and the depths it goes to to further flesh out this game’s themes. The prison begins in a series of corridors flooded with water (assumedly that’s why the prison was shut down in the first place), ending in a deep, seemingly endless pit. James jumps down this pit, and another in a room turned on its side, and another, without care or caution.

Toluca Prison, exterior and interior.

Each of these areas is increasingly more and more decrepit, from the main prison area being torn apart, and containing a gallows area where prisoners would assumedly be hung, down to what might be a morgue, tiles grimy and disgusting, down to the very base of the prison in deep, rocky caves. The ambience swirls and seethes in increasing intensity. There are very few enemies in this area, but the game once again never fails to make you feel unsafe and uneasy.

Gallows, morgue, and another hole.

Here, you come across Eddie for the first time in a while. He’s sitting on the ground, holding a gun and sitting conspicuously close to a corpse again. He looks up at James, and in one of my favorite quotes, muses to himself, “Killin’ a person ain’t no big deal! Just put the gun to their head…pow!”

He tries to explain himself, saying that the guy came after him, but soon changes it to being the man was making fun of him with his eyes. James, of course, tells him how terrible a justification for murder that is, but Eddie doubles down. “‘Til now I always let people walk all over me,” he says. He mentions a dog that had it coming too, and James seems horrified. Realizing this, Eddie backtracks and says it was all a joke. He leaves, markedly more confident than before.

“Killin’ a person ain’t no big deal! Just put the gun to their head… pow!”

Eventually, James gets to a long elevator ride that takes him down to the second, more important part of this area: The Labyrinth. While this is largely my least favorite part of the game to play because of how confusing it tends to be, it’s a masterclass of disorientation and surrealism, and is the place where Silent Hill 2’s uncertain reality becomes most distinct.

The Labyrinth

This is the one area of the game where you don’t get a map, James simply fills it out on his own as you progress through it. The upper level consists of dim corridors aesthetically similar to the interior of the apartments, but with a hardwood floor all across, and a flooded lower level carved out of the surrounding soil. Pyramid Head will begin appearing normally in the lower levels, and has swapped out the Great Knife for a spear. You can find his room filled with corpses, blood, and a giant metal fan, much more aesthetically similar to the first Silent Hill, in which you can get the Great Knife and wield it yourself. The Labyrinth begins with a room in which the entire room needs to be rotated in order to progress, and with this comes the game’s most iconic scene.

Pyramid Head’s crib.

Maria, somehow still alive, sits in a jail cell. James is dumbfounded, but Maria doesn’t even remember her supposed death, asking if he’s confusing her with someone else before calling him forgetful. She mentions a hotel in which she and James supposedly made a videotape, but James remembers having made it with Mary. James, likely as confused as the player, questions if Maria is Mary. She says she isn’t, but can be whatever James needs her to be. “I’m here for you James. See? I’m real,” she says, reaching through the bars to touch his face. She asks if he wants to touch her, but James seems hesitant at best. “I can’t do anything through these bars,” she says. “Come and get me.” James worriedly agrees and tells her to stay right where she is, and continues through the Labyrinth.

This is probably the single most cinematic scene in the game, and one of the best horror scenes in any game ever. The unnerving feeling of confusion that Maria is even here, let alone that she’s pretending nothing at all is wrong synergizes with her stilted, calm voice. She shifts between concerned and flirtacious, the lighting shadowing her eyes making her much more menacing in spite of her caring demeanor, and her voice tilts from ditzy playfulness to deadly seriousness from sentence to sentence. You sit on one side of the bars, free, and yet in most shots it almost looks like James himself is trapped, both physically and mentally. There’s always this odd sexual tension that the player themselves, as well as James, have no interest in, but Maria’s insistence of being perverse brings a lot of discomfort to the scene. It’s one of this game’s best displays of being intensely unnerving while never having to be directly scary.

Abstract Daddy

James soon after comes across a newspaper that talks about the murder of Thomas Orosco, Angela’s father, after which Angela’s frightened voice can be heard, crying “No daddy! Please don’t!” James runs to the source of the noise and bursts into the room. Angela has been backed into the corner of the room by a monster called Abstract Daddy, a mass of flesh that resembles two human figures; the larger one is on top like a man hunched over, while the lower one, a small, almost phallic figure, has a mouth on the end of it, periodically opening and closing. The flesh rests inside a bedframe, held up by legs, and attacking via outstretched arms, almost seeming to reach out for help.

The boss room appears to have fleshy walls with holes into which pistons thrust, and at this point the insinuation becomes obvious. Angela was sexually abused by her father. Outside material also insinuates that her brother also took part in this. Her mother didn’t help, telling Angela that she deserved it, and eventually abandoned the family, which is why Angela is searching for her throughout the game. Thomas had a history of drunkenness and violence, which may explain her mother’s actions, likely just as afraid of the man as Angela was. Angela eventually snapped and murdered both of them, leading her to Silent Hill, where her mother may have lived.

Abstract Daddy.

James fights the monster and mortally wounds it. He offers a hand to Angela, who refuses and gets up herself. She begins kicking the creature, before picking a TV in the room and smashing it over its head, dealing the final blow. James tells her to calm down, making her even angrier and accusing him of ordering her around, trying to be nice to her to use her, only after one thing. She begins to break down, saying that he could always just force her like “he always did.” James tries to reach out, but she yells at him not to touch her, calling him a disgusting pig.

She finally stands up and asks James about Mary, but calls him a liar after he says she was sick. She goes even further and accuses him of wanting her gone and going out to see other women before leaving once more. James scoffs at how ridiculous her claim is before setting off to the end of The Labyrinth. He gets to Maria’s room finally, but finds that she’s been killed again. He questions why, before sadly muttering, “Mary…” to himself.

Before long, James comes to a graveyard. Here, you find the grave of Walter Sullivan, a murderer mentioned in a newspaper clipping earlier (as well as a character who would become very important in Silent Hill 4), alongside the graves of Eddie, Angela, and James himself. James makes one last jump into his own grave. At the end of a long, blood-soaked hallway, in a cold blue room, James finds Eddie surrounded by bodies.

The second death of Maria, the final hole, and the bloody hallway.

The Meat Locker

James asks what happened, and Eddie doesn’t hesitate to tell James he killed them all. He talks about how his bully would call him ugly, fat, and disgusting, and always laugh at him. He's decided he’ll simply kill anyone who laughs at him. As he puts it, “It’s all the same once you’re dead! And a corpse can’t laugh.” James makes the error of asking if he’s gone nuts, and Eddie turns to him, accusing him of laughing at him behind his back too, shooting at him. This begins his boss fight.

After shooting him a few times, he’ll run into the next room, a meat locker. All of the hung up corpses have shorts on, and appear to be more human than normal. He talks about how he’s been tormented his entire life, picked on just for the way he looked, and eventually broke. He shot his bully’s dog, describing the horrifying way it died in glee, before he shot his bully in the leg and ran, finding himself in Silent Hill soon after, picking up Laura along the way.

James says he needs help, but Eddie snaps back, “Don’t get all holy on me James!” He, too, was drawn to the town for a reason, and Eddie believes he’s no different. Eddie comes out from hiding with a “Let’s party!” and the fight resumes, with James ending up killing Eddie, his first human kill. He’s horrified at himself, but begins to think back on Eddie’s words. He questions if Mary really died three years ago before finally exiting the descent of The Labyrinth. If you check Mary’s letter, it’s gone blank.

Eddie’s boss fight, Otherworld, and death.

James finds he’s somehow come out at a dock despite having traveled what seemed like miles down. Knowing where he needs to go, he finds a boat and begins rowing across Toluca Lake to the Lakeview Hotel. Rowing is often a little confusing and isn’t explained at all, so it took me, and apparently a lot of other people, a while to figure it out. While it does affect your ending ranking (something I didn’t mention in the first game, Silent Hills 1-4 have a star ranking out of ten depending on different factors for each game, and give you bonus items for New Game Plus), the boat ride mostly serves as a moment to reflect.

You row across the foggy lake, and consider everything that’s been said so far. You can no longer go back to the town, and Mary awaits you, but everything just feels wrong. The letter is gone, Eddie is dead, and James is questioning his entire purpose for being here. This brief moment of reflections allows both James and the player to consider their positions. In the end, James has always known more than you, and even then, James doesn’t even seem to know himself terribly well. Before you get to question for too long, you arrive at the dock of the hotel to find your answers.

The Lakeview Hotel

The Lakeview Hotel in its unburned state, exterior and interior.

Though the hotel had burned down years ago in an accident, it appears to be completely normal, completely unchanged even by the otherworld. For most of the exploration part of the level, there isn’t much plot, giving you time to process the story to this point before the climax. In the meantime, he has to collect three music boxes in order to get up to the third floor where James and Mary stayed on their vacation, in Room 312. He briefly encounters Laura, who finally shows James a letter she received from Mary to be given to James after he died.

Laura was an orphan and ended up in the hospital, where she met Mary through their shared nurse. They bonded in the time that Mary had been alive, to the point where Mary was like a mother to her. Before Mary died, she wrote a letter to be given to Laura after she died that said that she had gone to a “quiet, beautiful place,” which Laura interpreted as being Silent Hill rather than Heaven, unknowing Mary was dying.

It says that Mary had intended to adopt Laura had things worked out differently, loving Laura like her own daughter. She says to give James a chance (“I know you hate him because you think he isn't nice to me, but please give him a chance. It's true he may be a little surly sometimes, and he doesn't laugh much. But underneath he's really a sweet person.”), and wishes her a happy 8th birthday.

James immediately asks how old Laura is, and she says that she turned 8 the previous week, meaning that Mary couldn’t have died three years ago like James thought. With this, Laura runs off to look for another letter for James. James takes a moment to think, before continuing on his search for the music boxes.

Laura plays the piano, and gives James the letter.

Top

The Music Box

After he collects the videotape he and Mary made in an office, he collects all three music boxes, themed around Snow White, Cinderella, and The Little Mermaid, and places them in a larger music box. Placed in the right order, they play and the stairs leading up to the third floor open up. The melody that played, I think, was the moment that confirmed how much I love this game.

It’s a relatively insignificant moment, but it also marks the beginning of the end. This quiet, tiny moment of melancholy, soundtracked by one of the most tragically beautiful songs in the game, is your last moment of peace.

For a moment, there are no monsters, no deteriorated otherworld, just you, James, and the music. This is the end, and those stairs will take you to the truth you want, you know that. In this moment of peace, you prepare for an answer that you may not be ready for. Silent Hill 2 mastered anticipation and reflection in a way very few other games have, and, in spite of being unthreatened by monsters and nightmares and darkness, this moment of quiet, subtle sadness was the most tense moment in the game for me.

The Video Tape

Ultimately, you must leave your sanctuary and find Mary, so James walks up the stairs and finds Room 312. Mary isn’t there. Unchanged from when he visited, a TV with a VCR player sits against the window. A chair sits facing it, and James inserts the tape and takes a seat.

The videotape begins from James’ perspective. He’s filming Mary on their vacation in the room, talking about how beautiful the town is, making sense as to why it was a sacred place. She asks James to promise to take her back again, but begins coughing, likely being at the beginning of her illness. The screen begins to flicker to another shot of James standing over Mary in her bed. Her hand moves to his, either swatting him away or patting him in reassurance. He kisses her on the forehead, lovingly staring at her.

And then he smothers her with a pillow.

In what still remains one of the most disturbing scenes, and greatest twists, in any horror game, you find the truth of Mary’s death. There’s no blood and gore, nor is there any audio, just the buzz of the tape. Originally, you would have heard her screaming and struggling, but it was cut, once again choosing quiet horror where lesser games would choose much more graphic terror. The video flashes between the former shots of Mary and distorted, fuzzy footage of the smothering before it fades fully into static, and then back to James, sitting in his chair.

James sits in his chair, horrified, dejected, and silent. For nearly a minute, the camera circles around, and you’re left with the sad piano music and your own thoughts for that brief moment. This twist changes everything you know about James, about your journey, and about the relationship between character and player. James, as I’ve said, always knew more than you, but in a way, he also knew just a little as well. This repression of a terrible act made him, in his own eyes, an innocent everyman looking for his wife, not unlike Harry’s search for his daughter in the first game. Now, knowing what he did, the entire context of this nightmare crumbles, and you both have to face the truth for the first time.

Laura enters the room, asking if James found Mary. He tells her that Mary’s dead, which she believes is a lie at first before James gently, and straightforwardly, says it’s true. Laura, for once, becomes serious, and accepts it, asking if it was because of her sickness. James tells her the truth, immediately angering her and seemingly proving all her accusations of James not caring about her right. James barely reacts to her berating and hitting him, and she transitions from anger to sadness. She asks why, but he doesn’t even have an answer, and just apologizes mournfully. “The Mary you know isn’t here,” he says, standing to face her. Laura turns and leaves wordlessly, the last we see of her except for one ending.

James settles back into the chair, but after a moment his radio goes off, and through it comes the voice of Mary, loud and clear.

“James! Where are you? I’m waiting. I’m waiting for you. Please come to me. Do you hate me? Is that why you won’t come? James! Please hurry! Are you lost? I’m near. I’m waiting nearby James. Please. I want to see you James. Can’t you hear me? James… Please James… James… James… James….”

We may know the truth about Mary, but the town isn’t done with James yet. Leaving the room, the hotel’s true appearance is revealed: a burnt out, flooded husk of a building. Reality is setting in fast, and the paper that Mary’s letter used to be on disappears, leaving only an envelope. The music once again begins to swirl dizzyingly as both you and James reel. Nothing really felt real for a time, and I still had no idea how to feel.

Exploring what’s left of the building, James comes across a tape and headphones that play audio of James first learning about Mary’s disease, which contributes to one of the endings.

The Burning Staircase

Taking an elevator down to the basement, James passes through the flooded bar and into the back corridors until he comes across a burning staircase, where Angela stands. A tragic piano reprise of the game’s main theme plays as she spots James. She thinks that he’s her mother at first, and cries out to him, relieved and overjoyed. Two bodies, strapped down under skin-like covers, lay castrated on the walls, representing her father and brother. James backs away, confusing her for a moment before she holds his face and she realizes it’s not her.

Angela says, “Thank you for saving me… but I wish you hadn’t. Even mama said it… I deserved what happened.” James says it’s not true, but the camera switches to first person and Angela retorts. In a response that’s both to James and directly to the player, she tells us not to pity her, that she doesn’t deserve it. Her demeanor quickly changes though, as she guesses that maybe we just want to save her, love her, take care of her, heal all of her pain.

As much as most of us would like to say we could, it’s an extremely difficult task to undertake. It takes a will and strength that most people don’t have to take care of such a damaged person no matter how much you care for them, and how much they deserve to be taken care of. Just talking to someone and trying to sympathize isn’t always enough.

To get someone the help they need and to have the self-stability to be by their side through their emotional journey is something that will affect both of you. Though we all want to say, “yes, I’d be there for you always,” having the compassion and emotional fortitude to actually do so is so much harder than you might think. James certainly can’t, and I don’t think I would have been able to either.

“That’s what I thought,” she says.

Switching back to third person, she demands her knife back, which James denies. “Saving it for yourself?” she almost jokes. James denies it. He’d never kill himself, of course. But then, he’d probably also never kill a person, would he? Angela turns around silently and walks up the staircase through the flames.

“It’s hot as hell in here,” James says to himself.

“You see it too? For me, it’s always like this,” she says, before continuing up and off into the flames. We never see her again.

Pyramid Heads

James makes his way through the rest of the basement, the droning score by subtle heartbeats. He comes to a set of enormous stone doors leading to the lobby and enters. The music begins, at first a clanking, industrial sound, before James looks up and a grand choir comes in. Maria is strung up on a bed frame, two Pyramid Heads by her sides, one for Mary’s death, and now one for Eddie’s, or possibly representing Mary and Maria. James knows what’s about to happen, and begs the monster not to hurt her, screaming as one of them stabs her, killing her once again. James falls to his knees, defeated, but comes to a realization.

“I was weak.... That’s why I needed you... Needed someone to punish me for my sins….” Pyramid Head, inspired in James’ mind by the executioners of the past, is a representation of James’ guilt. Over and over again, he’s murdered an idealized, perfect version of Mary, assaulted and killed numerous monsters, all but himself feminine, and tirelessly followed James. In a way, he’s been as much of a punishment as he’s been a help, trying to show James the truth. James’ ability to get the Great Knife, one half of a pair of scissors, further cements this dichotomy.

James and Pyramid Head are two halves of the same coin, the crime and the punishment, the man in denial and the monster of truth. But now, James knows what he’s done. He doesn’t need Pyramid Head anymore, and as such, it’s time to end things.

The Twin Pyramid Heads.

The boss fight against the two Pyramid Heads isn’t particularly complicated, consisting mostly of the two monsters stumbling towards you with their spears while you shoot at them, running from corner to corner. If they do manage to hit you, they do huge amounts of damage, and if you’re too greedy getting cornered is possible, but as long as you get a few rifle shots in before he gets too close it isn’t too hard. After doing enough damage, the Pyramid Heads will walk to the center of the arena, hold their spears to their necks, and impale themselves on them. Their jobs are done. The envelope that held the letter disappears.

James inspects their bodies, and finds they’re holding two eggs, one rust-colored and one scarlet. As far as I’ve seen, most people see these eggs as representing new (the vibrant scarlet) and old (the washed out rust color), possibly the more recent death of Eddie and his fresh scarlet blood or the slightly less recent death of Mary, long enough for her blood to coagulate and become more of a rust color, or Maria being newer and fresher (scarlet also representing lust) and the rust representing the older, less lively Mary. It doesn’t really matter, nor has it ever been elaborated on, but it’s an interesting point of speculation.

Regardless, James places the eggs in slots on the sides of the doors and continues. Passing a door with a tormenting looking face on it that scared the shit out of me the first time I spotted it, he finds the final corridor. While you walk down the long hallway, you hear a conversation between Mary and James.

James brought her some flowers, but she yells at him about looking like a monster undeserving of flowers, and yells at him to leave over and over. She says she wishes they’d just put her out of her misery. She tells James to go one more time, and not to come back, and he listens. Immediately, she cries and begs him to come back and tell her she’ll be alright. “Help me,” she says, as the conversation ends. It’s all heartbreakingly sad, with Mary’s voice acting being genuinely phenomenal.

James finds himself at the foot of a metal stairway in the rain leading him what seems like infinitely up to the roof of the building, the structure immediately falling out behind him when he gets to the top. Finally, there she is. Mary stands, looking out the window into the foggy sky. What she says varies immensely between which ending you get, so I’ll go over them all separately.

Endings

There are three main endings, “In Water”, “Leave”, and “Maria”.

“In Water” and “Leave” have slightly different dialogue but the point is mostly the same. The woman appears to be Mary, but is still just Maria. James says that he doesn’t need her anymore, but Maria begs him, saying she can be everything Mary never was. James denies her still, infuriating her.

In the “Maria'' ending, she says that she is indeed Mary, and sits in a bed. Peaceful music plays, and James apologizes for taking so long, wanting even the slightest vision of her. He tries to say that he killed her out of mercy, but she says that she was just a burden to him, and resented her. He admits he did sometimes have those thoughts over the long three years she was sick. She asks if that’s why he needed Maria, and refuses to forgive him, angered.

Mary.

Either way, Mary/Maria transforms into the final boss, writhing and twitching, almost glitchily becoming monstrous (resembling the deleted Jacob’s Ladder scene in which a certain character becomes a monster as well). She appears dressed in a nurse's outfit likely representing her hospitalization, and her skin becomes corpse-like. She hangs upside-down in a metal frame like Maria minutes earlier, with twisted, squirming spikes at the bottom alongside a long black tentacle that strangles James if he gets too close.

Other than the tentacle, she attacks James with swarms of moths. Moths and butterflies appear a lot in this game, moths typically representing death and rot while butterflies represent rebirth. Moths also appear earlier in the apartments while Maria, Mary reborn, has a butterfly tattoo. Mary herself likely feels as though she was decaying while she was sick, practically already dead. The fight, again, isn’t too hard, just keep your distance until her moths go back to her and then shoot, or simply wait five minutes.

Mary, the final boss.

The monster falls to the ground, and it calls out one last time to James, and with one last hit, she dies, the screen fading to black. You fade back in somewhere else.

In “Maria'', you appear on the boardwalk on Toluca Lake. A woman asks if James killed Mary again, to which he says he knows it wasn’t really her. To his shock, though, the woman is Maria. James says he wants her to be with him, seemingly having learned nothing. They go back to his car, and she begins to cough, the cycle repeating and the delusion continuing.

In both the “In Water” and” Leave” endings, James and Mary appear in a bedroom.

In “In Water”, Mary says that she wanted to die, to be rid of her suffering. James says that’s why he did it, before admitting that wasn’t really the whole truth and that she said she wanted to live too. He says that he partially did hate her for taking his life away. She says that he suffered enough for his sins. She then coughs, and dies once again. He carries her body out of the door, and the screen fades to black.

You hear James say to himself that he now understands what he came to do, having nothing without Mary. Audio of a car rapidly speeding up suddenly cuts out, and James says, “Now, we can be together”. The screen cuts to an underwater shot, James having driven himself, and the body of Mary, into the lake, finally joining her in death.

In “Leave”, the dialogue is mostly the same, but after James says that he wanted his life back, in one of the most heartbreaking lines in this entire heartbreaking game, says, “James… If that were true, then why do you look so sad?” Mary asks one last thing of him: to move on. The screen fades to black, and then back into the foggy graveyard where we first met Angela, and Laura passes by. James follows, seemingly taking up Mary’s wish to adopt her and moving on, though how he convinced her to go with him is unseen.

During all three endings, Mary or Maria hands James a letter that’s read out during the final shot (The parking lot in “Maria”, underwater in “In Water”, and the graveyard in “Leave”). This is the real letter that she wrote to him before she died, the one he was supposed to get after she passed away. It’s too long to write out, so I’ll just leave a video and audio of it, but in these final moments of the game, it was difficult not to well up. It’s so well acted and emotive and convincing, and so ridiculously sad after everything you’ve gone through. Without fail, “James… you made me happy,” gets me teary-eyed, and apparently the voice actress, Monica Taylor Horgan, cried after reading it, which you can hear in the final moments of it.

There are three other endings only obtainable on a second playthrough, two jokes and one more as a tie-in to the more occultish elements of Silent Hill lore.

The Dog ending sees James find a key in a doghouse early on, and using it on a specific door near the room where he finds the truth about Mary. Behind it is a Shiba Inu named Mira at a giant computer flipping switches and pushing buttons. James falls to the ground, and in Japanese (done by the English voice actor, Guy Cihi) says “So it was all your work…!” The dog licks his face and the credits, a hilarious montage, plays, with goofy music in the background.

The U.F.O. ending, which is only in re-releases of the game and not the original PS2 version, is actually a sequel to the U.F.O ending in the first Silent Hill, making this technically the only real story connection between the two. Getting a blue gem and using it in certain spots in the game, instead of playing the tape in Room 312, U.F.O.s will appear at the window. It’ll fade to a black and white scene with Harry Mason, in his full blocky PS1 glory, working alongside the aliens. As goofy old sci-fi film music plays, he’ll ask James if he’s seen his daughter, and James, very confused, will ask if Harry’s seen his wife. However, an alien zaps James in the back, knocking him out, and they abduct James. The credits play, styled like an old film.

The only serious optional ending is the third, “Rebirth.” With all the themes of rebirth, between the butterflies and possibly the Pyramid Head eggs (eggs tend to symbolize birth), this ending does make thematic sense. After collecting three ritual items throughout the game, it plays out like a shortened version of the “In Water” and “Leave,” with Maria as Mary being rejected by James and fighting the final boss. After this, however, it cuts to a completely new scene.

Eerie ambience plays as James rows across Toluca Lake, his wife’s corpse laying on the floor of the boat. He apologizes for having to wake her, but simply can’t go on without her. “This town, Silent Hill… The Old Gods haven’t left this place. They still grant power to those who venerate them. The power to defy even death. Ah… Mary,” James says, talking to her body. The camera ominously pans over to a small island with what looks like a mysterious chapel on it. The screen fades to black.

The actual canon ending of the game is unknown. Staff that work on the game generally seem split between “In Water'', which is the most popular since it fits the most with the somberness of the rest of the game and was used in the novelization’s ending, and “Leave,” which makes just as much sense in the larger Silent Hill universe. The only clue as to the fate of James is the appearance of his father, Frank Sunderland in Silent Hill 4, who says that his son and his wife went missing, meaning James never returned home. Again, one doesn’t really outweigh the other in terms of evidence, so it’s up to interpretation.

In my playthrough, I was actually surprised to get the “Leave” ending. At first I agreed that “In Water” generally seemed more fittingly depressing, but I think after all was said and done, I didn’t want this story to end sadly. It’s a love story just as much as it’s a tragedy, and a Romeo and Juliet style double-death I didn’t feel had the poignance of “Leave”’s bittersweet sendoff. James is one of the most sympathetically written murderers in any story ever, and I think how much you sympathize with him largely determines which ending you prefer.

Crime and Punishment

Silent Hill 2 is largely based off of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s book Crime and Punishment, which deals with how murder effects the psyche and how something so terrible can completely skew one’s morals. James’ entire journey is like a psychotic fever dream in which ever single aspect of it is designed to torture him and make him guilty. Every monster other than Abstract Daddy is directly connected back to James’ and Mary’s psyche.

The Lying Figure is how Mary sees herself. It uses vomit to attack, being sickly in nature, and appears trapped in its own skin. The Bubblehead Nurses represent Mary’s hospitalization and James’ unfulfilled lust while he was ill. The mannequins are literally just two pairs of feminine legs attached at the hip, and appear in a scene where Pyramid Head assaults two of them in what isn’t explicitly sexual, but clearly creates a very provacative image, intended to disturb the player as, according to CGI director and character designer Takayoshi Sato, sex and death are at the very core of human thought.

Maria in particular is designed to be this perfect, libido-driven version of Mary that the designers made with the intention of being uncomfortable in her perfection. She’s the antithesis of a strong female protagonist on purpose: highly sexualized, dependent on a man to be saved, always doing the most to take care of him, and incredibly ambivalent in her motivations, easily swayed one way or the other. She’s a perfect woman from a completely male gaze intentionally. Takayoshi Sato described her as such, and compared a perfect person to someone who may appear more flawed. When you take a photo of them, they may have a slightly odd smile, but that small bit of human imperfect makes them that much more real. Maria’s perfection makes her so much less so.

However, as with her real counterpart, all the flaws are in the details, yet in her perfection she doesn’t try to hide it. She isn’t completely skinny, but wears a crop top anyways. She has a lot of darker patches around her neck and chest, but doesn’t wear concealer. Even her hair, which naturally would be brown, is dyed blonde with a hint of red at the ends for a bit of a streak of extra appeal. Despite appearing perfect, when inspected on a closer scale she appears more like a woman desperately trying to make themselves perfect, like Mary trying to make herself into the woman James seemed to want her to be. She feels unreal because she is, both metaphorically and literally: a real person trying to become perfect, and making themselves less real in the process.

The other two main characters, Eddie and Angela, are also dealing with the guilt of murder, on different spectrums of morality. Whereas James is morally grey, Angela is pretty thoroughly justified, killing in self-defense after being physically and mentally tortured for most of her life in a way that makes her paranoia and misandry all the more sad and understandable. Eddie, while still feeling somewhat tragic in his torment, was much less sympathetic considering he took out his anger on an innocent dog and thoroughly enjoyed the act of killing, justifying it to himself compared to the shame James and Angela feel.

These different levels of morality all come together right before you begin jumping into the holes in Toluca Prison. As previously mentioned, there are four gravestones: one for James, Angela, Eddie, and Walter Sullivan. You’re all killers, and you’ve all dug your own graves. In the end, they’re all murderers, and they’ll have to jump into their graves eventually. However, forgiveness is also a huge theme of this game. Eddie and Angela cannot forgive their tormenters, and are tragically overcome by their mental torment. Meanwhile, James’ mind and Pyramid Head serve as his tormenters, but unlike the others, it’s up to player themselves whether or not to forgive James.

In all this guilt, this constant suffering between the two lovers, the otherworld creating a living nightmare of his own creation, and of course through a being created for the sole purpose of punishing him with Pyramid Head, James gets his punishment. As Mary says in “In Water,” it’s enough. I think falling onto one side of James killing Mary over love or hate is way too simple for such a well thought out and complex game, and I think “Leave” best reflects both sides of this.

James has been punished, not by the law, but by the will of the town, and served his metaphorical time. Clearly, he did love Mary, but he did also undeniably resent her to some extent and felt repressed, emotionally and physically, selfishly. All of the game's imagery and displays of suicidal ideology and many of the things James says, and ultimate does in the “In Water” paint a picture of a man racked by depression and guilt with no will to go on anymore.

He’s not an innocent person, but he also presents as well-intentioned, trying his best to help where he could in the depths of Silent Hill, and caring for Mary despite her largely taking out her frustrations on him, loving her until the end. In every ending, Mary’s letter always tells James to move on and live for himself, and “In Water” just feels like such a denial of her wishes, while “Leave” feels like a true fulfillment of James’ story as a story of the ultimate crime, its suitable punishment, but ultimately redemption in the face of sin.

(Summary Ends Here.)

Silent Hill 2’s story is, without a shadow of a doubt, the best part of it, and the best the series has ever seen. I’d argue it’s one of the best told stories in any game ever made, and is the gold standard for how to make an emotionally effective narrative in this media, the only on par example I can think of being NieR Replicant, which hopefully I’ll get to soon.

It had such a ridiculously huge impact on this series, and the psychological horror genre in general, that most other games in this vein are almost obliged to have a giant game-changing twist, from Dead Space to Cry of Fear to the The Evil Within games to Omori, the list goes on and on.

Obnoxiously, it also became a bit of a trademark of later Silent Hill media to take monsters from this game and slap them around wherever, regardless of if it makes sense, but I’ll cover that in the movie and Homecoming especially.

Sound and Music

However, story isn’t the only strength Silent Hill 2 has. I’ve very lightly touched on it, but Silent Hill 2 has fantastic sound design and music, just like the first game, but this game has a much different tone. Silent Hill 2 is a lot more quiet and melancholy. I would say the majority of the soundtrack, once again done by the fantastic Akira Yamaoka, is the aforementioned trip-hop combined with a lot of alt-rock.

The main theme of Silent Hill 2, “Theme of Laura”, is every single moment of this game bundled into 3 minutes and 24 seconds of song, and is by far my favorite track in the series. It has this overwhelming, wistful sadness to it, while also having heavier moments of darkness, usually overlapping. It’s sad and lonely sounding, but also has this powerful sense of hope radiating through it. It's a really incredible song and it’s no wonder it’s probably the most iconic theme in the series.

The trailers for the game also have different versions of the song, with the one from the 2000 Tokyo Game Show (I would guess the first announcement trailer) being a lot more acoustic, while the 2001 E3 trailer was mostly the same as the in-game version, but also had a guitar solo that has never had an official clean release sadly.

Other tracks go for more of an ambient sound, like “The Day of Night,” or “Laura Plays the Piano,” or infuse trip-hop into Silent Hill 2’s ghostly atmosphere with songs like “Heaven’s Night,” “Alone in the Town,” or “True.” Then there’s all of the game’s rock or piano-based songs, like “Wishful Thinking,” “The Reverse Will,” “Overdose Delusion,” “Promise,” and the reprises of “Promise” and “Theme of Laura.” There are way too many fantastic tracks to include, so I’ll just say listen to the whole soundtrack if you like the ones I’ve included here. It's one of the best in the series, though the following two games are just as phenomenal, not to jump the gun.

The more ambient tracks in particular I think separate this game from its predecessor. The first game is heavy and oppressive in its industrial noise without many moments of safety, Silent Hill 2 is much more calm and, like I said, ghostly. I would describe it as the difference between a visceral nightmare and a surreal dream.

All of the game’s sound effects were also done by Yamaoka. Beyond a lot of the incredible detail, like his uses of dozens of unique footstep sounds for a more real sound, Yamaoka also wanted a unique take on the monsters’ sound design. He describes Resident Evil’s monster sounds as somewhat formal, sounds that aren’t really that unusual to hear. He instead went for a sound that was surprising and unsettling, something completely abstract that got a direct reaction out of the player.

2 also has a lot of small random noises that may or may not occur based on RNG (random number generator, a system that can determine certain random events based on what frame you started the game on). In the apartments, just before crossing over, you might hear a strange whispering that is completely indistinct.

For years, people thought it might have said something about Mary, but it turned out to just be gibberish from a sound effect collection. Alongside this, a certain door may or may not rattle when you pass by it, you may hear the sound of a faucet turning on, and the entire third floor has a breathing sound as if the building itself has come to life. The prisons also house some kind of invisible monster that doesn’t attack, but loudly stomps around chanting, “ritual,” and in one of the bathrooms, if you knock on one of the doors, when you move to leave a woman will scream and bang on the door, but only sometimes.

These weird noises with no explanation and, alongside the dreamy surrealism of the game’s ambience and much softer music, give this game’s soundscape a deeply tense atmosphere where it isn’t just utterly silent compared to Silent Hill’s panic-inducing hellscape filled with cacophony.

Visuals

Graphically, Silent Hill 2 is leaps and bounds better than its predecessor obviously and hasn’t aged too terribly considering its been two decades. Whereas the genius of the first game’s fog and darkness was just a clever workaround for a small team working with limited hardware, the Playstation 2 was a different beast.

Monsters are much more animated, humans actually look like humans, and environments are significantly more detailed. A lot of small areas, like Heaven’s Night, are intricately detailed little environments that, in spite of their both narrative and functionless lack of purpose, put on display the sheer love put into creating a believable and lived in world. The lighting especially has vastly improved, creating much more harsh contrast between light and dark than the first game was capable of , and creating a lot of interesting aesthetical changes in environments through color choice alone. The PS2 version of the game unfortunately still had polygonally based lighting for the flashlight, but the Xbox and PC versions not much later were much cleaner looking, though those ports were also much less stable.

The town’s main street is based around San Bruno, California, with many buildings looking identical to buildings in the town. Being far larger than what the first game’s part of the city was capable of, there’s a lot of long stretches of practically empty roads with nothing but monsters. These moments, like the run to the Historical Society or the game’s opening walk through the forest create a sense of crippling loneliness, of helplessness almost. There are other people out in the fog, but they’re just as damaged and lost as you. In the end, you’re truly alone.

Silent Hill 2’s Neely Street in, and buildings in San Bruno, California; the buildings were slightly altered later on in development.

Alongside the in-engine graphics, Silent Hill 2 was also pretty groundbreaking in its use of CG cutscenes. In fact, it was one of the selling points of the game. While they’re aged, the CG was incredibly impressive for its time, with faces looking real, but also unsettlingly slightly inhuman, creating that near perfect uncanny valley as mentioned earlier.

Unlike a lot of other games of its time, it used a combination of motion capture for most of the movements, but specifically in the faces there was a lot of hand-animated moving parts to make the characters both more expressive and more unsettling, as well as making the lip synch just a little better than an average game of the time. Every character is also motion captured by the same person who voiced them, and modeled somewhat after their actors, giving them even more of a realistic touch.

Monica Taylor Horgan plays Maria, Guy Cihi plays James, and David Schaufele plays Eddie.

Many of the characters also have a lot of details that add to their characters. Maria’s aforementioned balance between perfection and flaw, Angela being designed to look a lot older than she really is and being played by Donna Burke, who was in her mid to late 30s despite the character being 16 or 17, and Eddie’s eyes moving a lot more than other characters’ and looking off slightly in different directions give a lot of insight into their psyches.

All of the monsters, designed by Masahiro Ito, were intended to each have a human element to them, and strengthened the idea of monsters having symbolism connected to the plot or characters. Compared to the first game’s animalistic or supernatural creatures, this game’s monsters are shaped more like deformed people. They’re given odd movements and weird body angles that contribute to this deformity. He also based a lot of his designs off of those of Francis Bacon, a painter known for his unsettling portraits of the human form that often incorporated geometric structures into his often formless bodies, similar to the designs of Pyramid Head, Flesh Lips, Abstract Daddy, and Mary’s final boss form.

Some of the works of Francis Bacon.

Pyramid Head in particular was designed with the intent of being made more inhuman with an odd head. Ito experimented with different masks, but figured he still looked too human, and decided to put the massive pyramid that gave him his name on. He describes the triangular shape to insinuate pain in its sharpness, which contributes to his role within the plot; these designs were also inspired by some of his older art school works.

Two Pyramid Head concepts, and Ito’s “Strange Head” works from art school.

The environmental design is a deterioration of familiarity, intended to repulse and attract players. Every inch of this game is designed to make you uncomfortable and disturbed, and all of its aesthetic design comes together to create this world that feels like a distortion of reality, with slight chances in the environment (the decrepit interiors of all the buildings, all the flooding, the darkness of the hospital) alongside the unnerving uncanniness of the characters, between their voice acting and appearances.

This even comes down to a lot of small details, like the fact that every corpse in the game uses James’ model, or the use of Mary’s dress on the mannequin where you get the flashlight that you wouldn’t even realize is hers unless you looked at her photo. It’s a beautifully detailed game and overcomes a lot of the criticisms of older games by having such strong art direction.

Terror vs. Horror

One complaint I do see frequently about Silent Hill 2 is that it isn’t really scary, especially compared to its immediate predecessor and successor, and while it is to me because horror games terrify me, I would have to agree that it isn’t really a downright terrifying game unlike the first game. I would, however, say it’s a much more horrifying game. Silent Hill made me jump and panic, and its primarily non-human enemies posed much more of a threat than many of the sequel’s much slower, humanoid foes. In the moment to moment gameplay it freaked me out significantly more, but Silent Hill 2 made me feel uneasy for weeks after I finished it.